We’ve come a long way since 1918

Google the phrase, “How the pandemic is changing…” and you’ll trigger a seemingly endless string of article titles that begin with those exact words: How the Pandemic Is Changing Banking. Exercise. Halloween. Sex. Relationships. Air Pollution Levels. Summer Camp. The Way We Eat. The Chemical Industry. Cholula’s Hot Sauce Bottle. Me. Us. Advertising.

Of course advertising. TV ads for cars, cell phone plans, windshield damage insurance, pet food, blenders, cosmetics and room deodorizers are expected to reflect the world as it now exists, not as it was…well, back when. That means no scenes of travelers sitting cheek by jowl in airport waiting areas, no crowds of millennials partying like it’s 2019 in the creative.

Advertisers understand this. Indeed, a World Federation of Advertisers survey earlier this year found that 89 percent of large advertisers had pulled planned campaigns that would have seemed tone-deaf during the pandemic. Today, ads are likely to offer useful information, exhort us to act prudently, move us deeply or show how products and practices have been adapted to how we now work, play, shop, vacation and socialize. The messages often meld acknowledgment and aspiration: Avoid crowds but stay connected. Face the crisis but stay upbeat. Or empathy: We get that your home has become the nerve center. The creative models the idea that you can take precautions, and enjoy life. “It’s a different kind of summer,” proclaimed one seasonal car campaign. “But it is summer.”

Admittedly, for some industries there’s honest money to be made from the pandemic. Really, is anyone surprised—or disturbed—by the surging demand for streaming services, sleep aids, work-from-home software, hand sanitizer and DIY food prep packages? The important thing is that ads not be seen as insensitive or exploitative. Which, overwhelmingly, they are not.

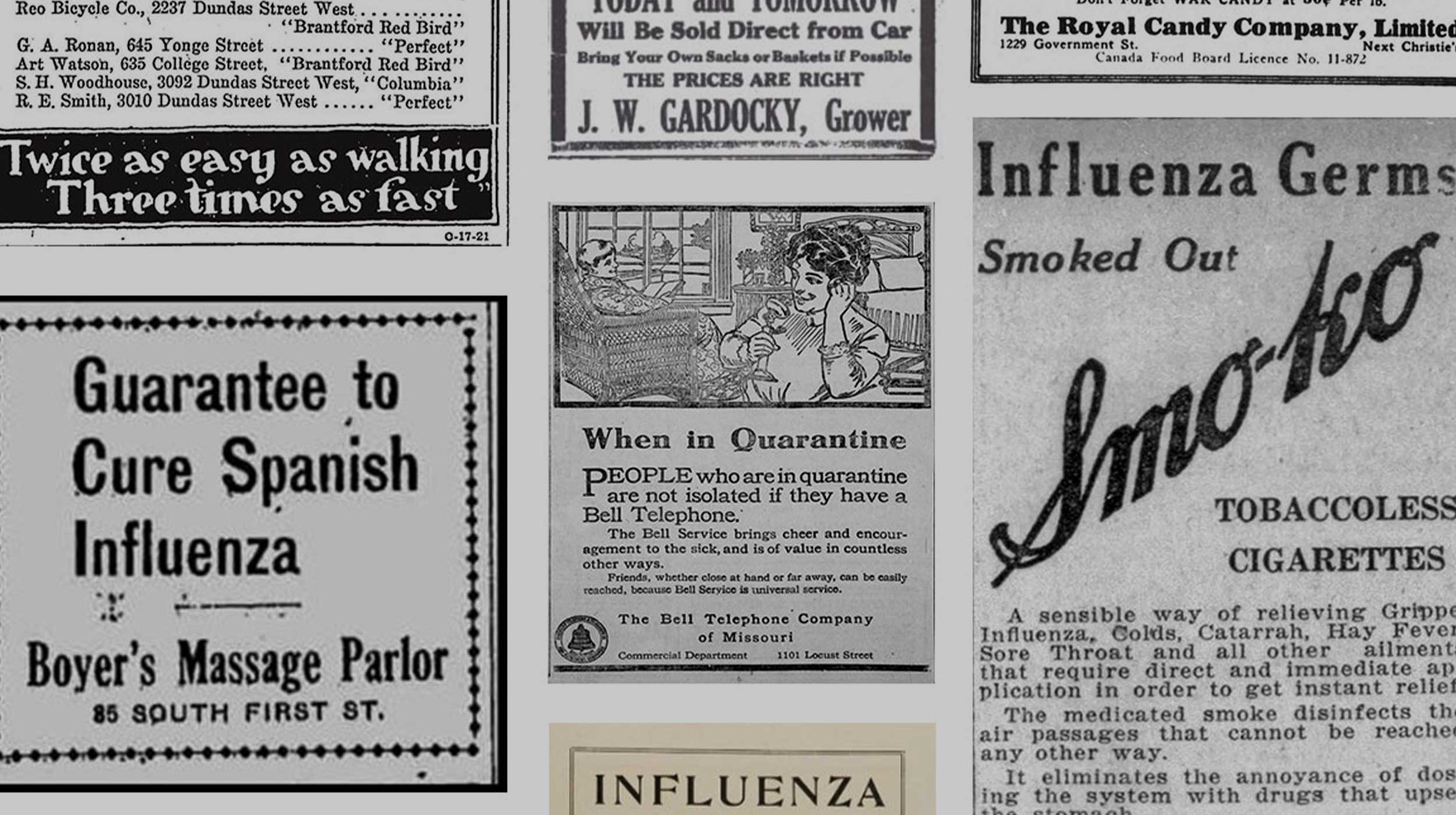

But that wasn’t the case during the influenza pandemic of 1918-19, when marketers were less than subtle about profiting from fears of disease or making false—and brazen—claims of efficacy. At Carpenter Group, we thought it would be fun to gather a sampling of pandemic-themed ads of the day. A century before “disinformation” entered our vocabulary, many advertisements pushed bunkum cures or preventatives, sick-shamed consumers for eating poorly, or fictionalized the life-giving properties of bicycles, onions and a good pair of dress shoes. Excerpts follow:

Bovril, by the way, is a salty meat extract paste that first appeared on UK grocery shelves in the 1870s. Drinkable when diluted with hot water, it remains a staple of many British diets. Importantly, like onions, fudge, beer and pianos, it is no longer advertised as a treatment for disease.